As a Learning & Development professional, Equine Experiential Learning (EEL) may have crossed your Leadership Development methodologies radar at some stage. But unless you’re an avid horse rider, it is unlikely that it held your attention for too long, seeming far-fetched and strange. In this 3-part series, I invite you to learn how EEL is a surprisingly effective way to develop leadership self-awareness, confidence, and people skills, even if you are not a horseperson. EEL is increasingly being used in the corporate world for leadership development due to the powerful and unique benefits the methodology offers not found in other avenues. Note that one does not need to have had any previous experience with horses to engage in EEL. In fact, it can actually be more advantageous to have no prior experience, as old habits, attitudes, and sentiments do not need to be ‘unlearned’. During an EEL session all activities are conducted on the ground; horses are not mounted or ridden.

***

My name is Ingela Troha and I have been working with SyNet since 2012, based in Australia. This is my story of a life-long involvement with horses that has led me, quite inadvertently, to profound personal psychological shifts in my life, some that even dragged me there ‘kicking and screaming’… As I reflect on who I am today, it is clear that horses have played a significant role throughout my life – in ways I never imagined. But first, I would like to take you back in time for a moment, to where it all began for me….

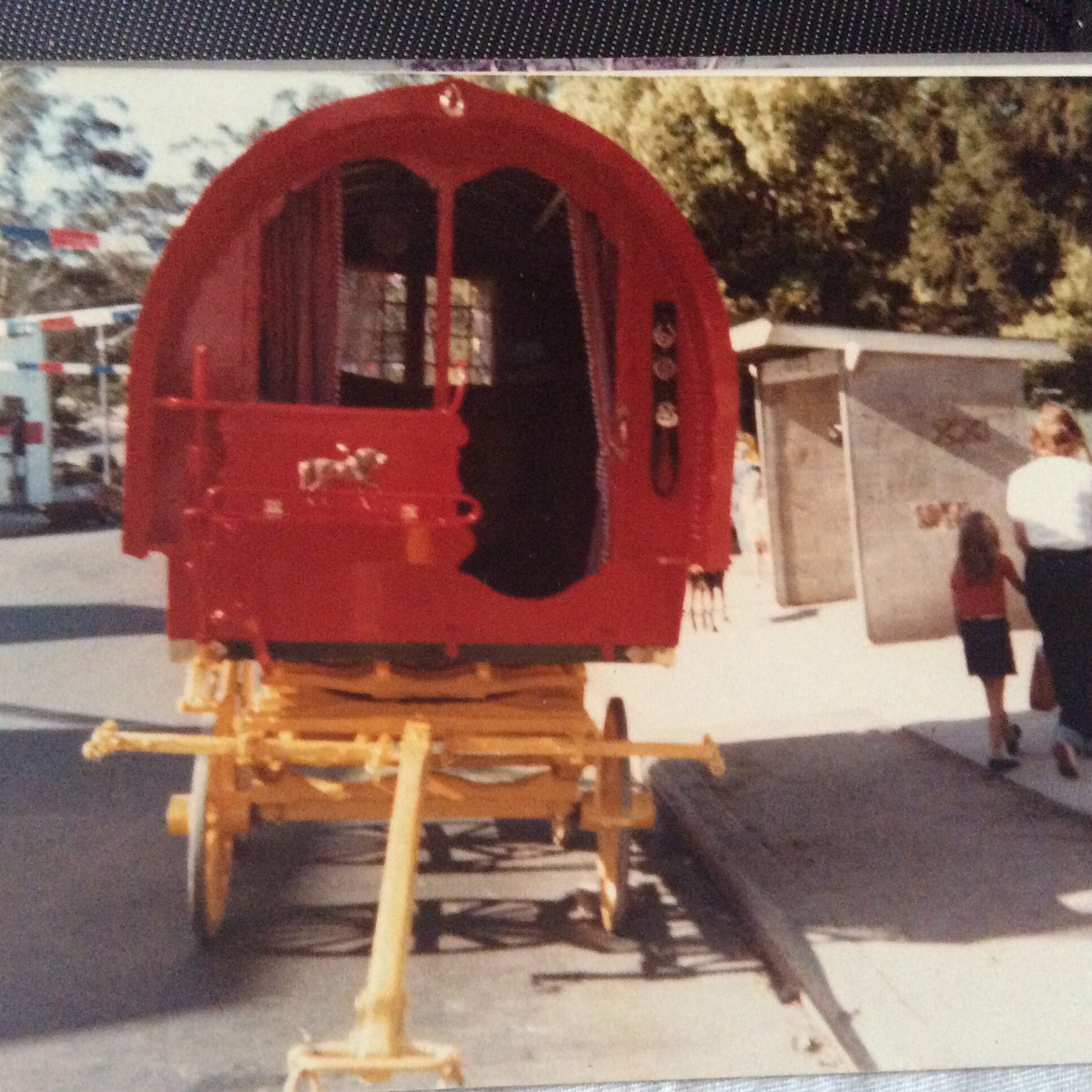

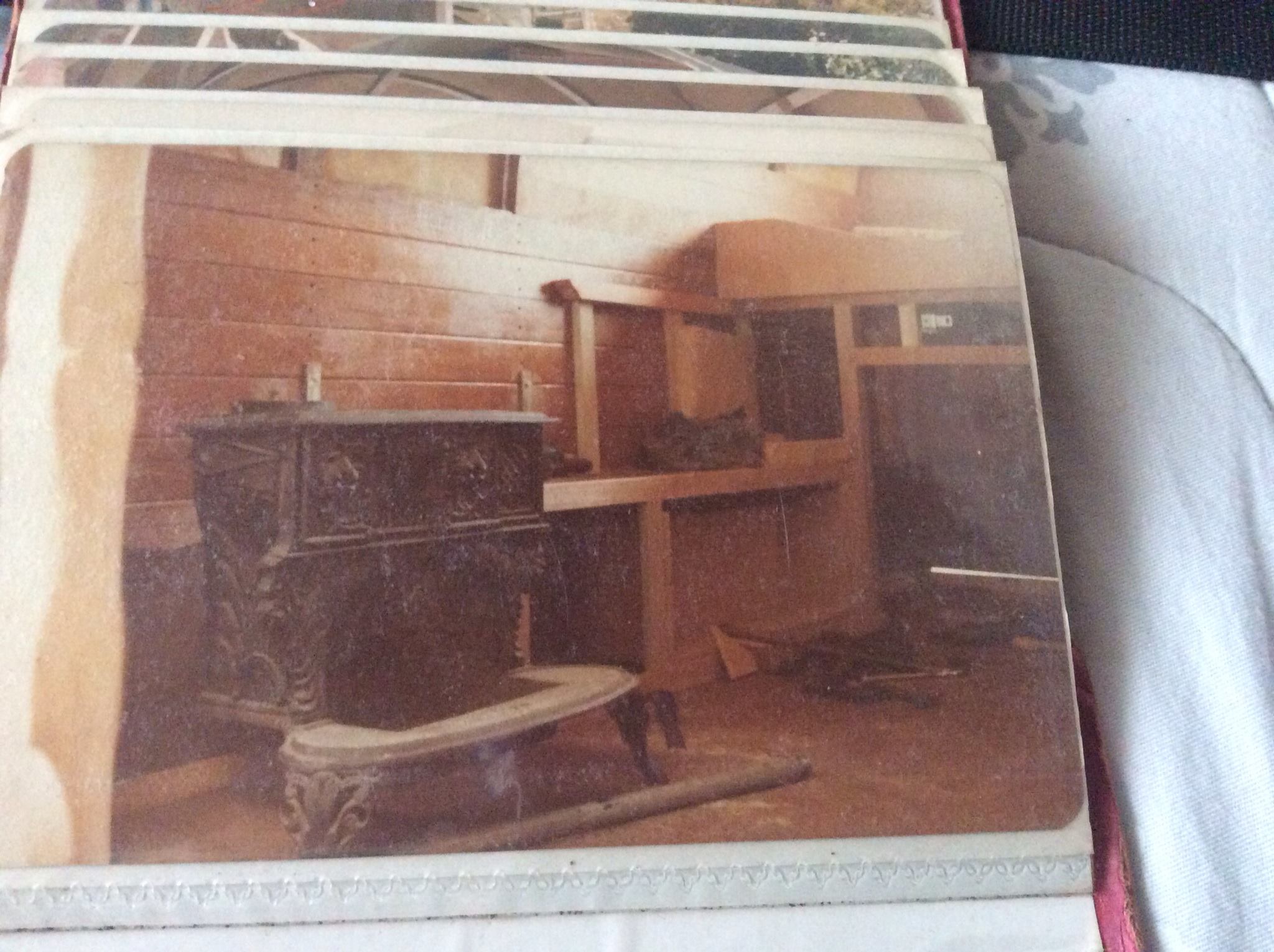

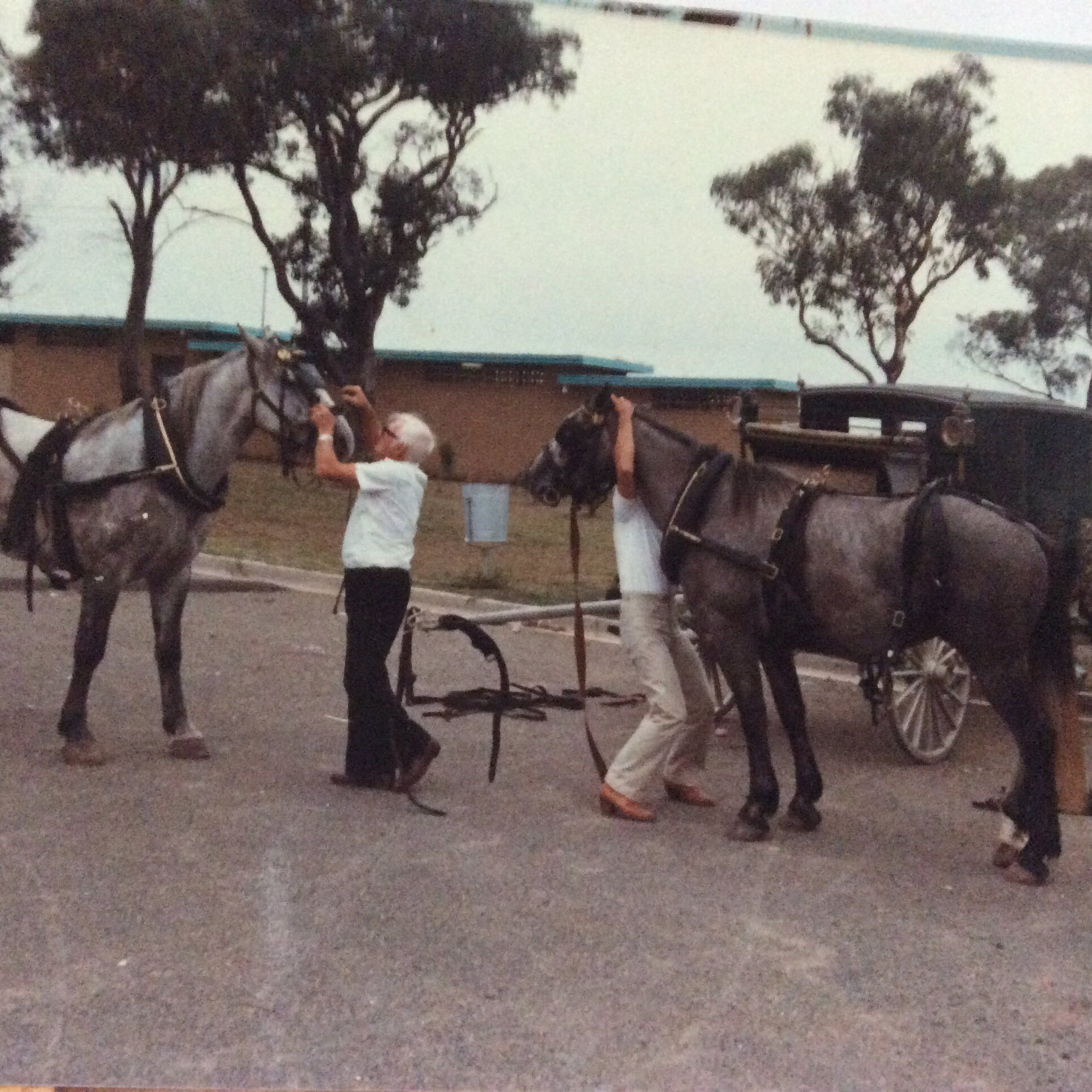

My journey with horses started when I was very young. When I was 8 years of age, my mother and stepfather followed their dream of travelling throughout Australia in a Gypsy wagon. Yes, literally a wagon – the kind you see in old Wild West movies pulled by a team of draft horses. It wasn’t a ‘caravan’ with mod cons made to look like a wagon either. We had no electricity and no running water. We cooked on an open campfire each mealtime or on the potbelly stove inside the wagon by candlelight or kerosene lantern. We only went as far and as fast as the horses could travel each day, sometimes not that far at all. In the wet seasons, progress would slow to a boggy crawl.

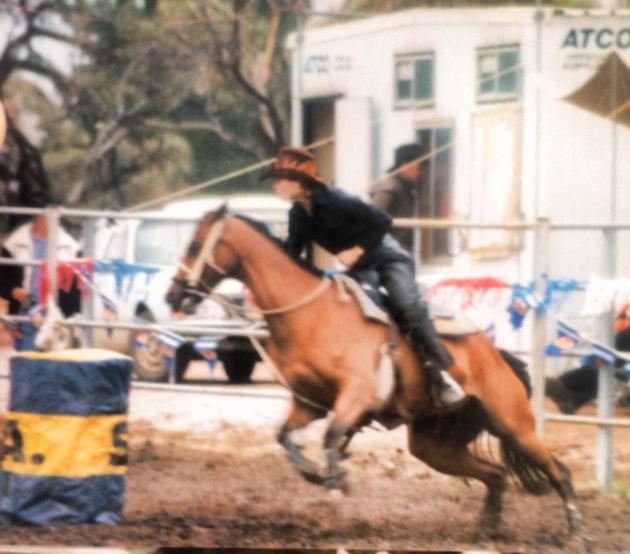

For a few years the horses were our life; they were our transport and therefore dictated the pace of living. We trusted and relied upon them implicitly. Finally we found ourselves at a horse stud farm in a small outback Australian aboriginal town. We lived on that farm for one year and it was the owners who introduced me to the world of horse breeding and competitions. Initially I started showing horses in Western Pleasure & Cutting. Then as my passion grew and we finally moved back to Sydney, I began competing in everything from show jumping, cross-country, dressage, hacking, and endurance. My favourites, however, were the fast sprint-racing horse events: barrel-racing at rodeos, bush racing, camp-drafting, polo and stock horse challenges. Later I also did track work exercising racehorses at Randwick Race Course in Sydney, fox hunting, horse treks, and cattle droving in the precarious Snowy Mountain terrain, virtually anything that allowed me to gallivant around on the back of a horse. Some of these terms may not mean much to you, but the common thread with all is that they are very demanding activities for both horse and rider, and many are done at extremely high speed, adding an element of thrilling danger. When I rode it was as though the horse was an extension of me, and I would feel super-human.

My equestrian experience grew, and with it my education of horse handling. But this is where my story sours somewhat, for the prevailing attitude of the day about horse training was based on a very harsh disciplinary attitude. If you had a problem with a horse, the solution was that the horse needed more ‘discipline.’ It was never the trainer’s issue or approach at fault. The horse’s problem was ‘fixed’ by using a harsher bit in their mouth, a curb chain, a drop noise band (similar to clamping their mouth shut), tying their head down, and ample use of whips and/or spurs.

Throughout those earlier years, I never came across any professional or hobby horse person questioning these practices, or handling their horse any other way. While not consciously recognised, the only solution ever considered in those years was to control the horse through force and intimidation, bullying and breaking their spirit. Not knowing any better, I went along. It was the ‘norm.’ Thinking back, trying to feel what it must have been like for the horse, I now see how my own lack of awareness kept my head stuck in the sand. I, too, never thought of changing the system, questioning the unnecessary mishandling, uncontrolled tempers, irrational behaviours, disrespect for the horse’s nature and psychology, and the inconsistent communication between rider and horse. That was how it was done. There was no heart, no spirit, no feeling for the horse or for developing a relationship that was anything but a gain for the human.

In my late teens, however, I was introduced to ‘natural horsemanship.’ Oddly considered as the ‘old forgotten’ method of horse training, my eyes were opened to how people and horses should communicate. As I became more open to experimenting with these different methods that were challenging the damaging conventions of the day I encountered far greater results with my horses than I had ever imagined possible, in not only an efficient, but also a calm and effortless manner. Instead of fighting against the horse, I was allowing a bond of deep communication to be established between us.

Natural horsemanship is not about fixing the horse… it is about fixing the human. And this was the beginning of my lessons in EEL. The mental shifts changed my approach from breaking the horse to partnering with the horse. I became more aware of my own conditioning, my emotional patterns of thinking and feeling, and my limiting beliefs as I moved into a greater awareness – seeing which thoughts and behaviours were non-serving.

Equine Experiential Learning has many parallel life lessons where humans have the opportunity to experience themselves through the eyes of a horse, to learn about deep communication, and to form close relationships of partnership and collaboration.

Stay tuned for PART 2 in the next issue… where we invite you to join us on this journey as we partner with equines to cultivate corporate leadership, teamwork and communication, creating emotionally intelligent leaders.

Join the conversation and tell us your thoughts and/or share your own experience of EEL.